Aerial shot of Congo basin peatlands. Daniel Beltrá / Greenpeace

This report is based on a joint investigation by Global Witness, Der Spiegel and Mediapart, in conjunction with the European Investigative Collaborations (EIC) media network.

- Claude Wilfrid Etoka, who manoeuvred out a rival to take control of the Ngoki oilfield, had company bank accounts closed down in France over corruption red flags, our investigation reveals.

- An environmental impact

assessment almost entirely pre-dated the peatlands’ discovery with no

analysis of the risk to peatlands from drilling – rendering it unfit for

purpose.

- There is evidence oil reserves have been wildly exaggerated and may not be economically viable at all.

Introduction

The oil-rig looks incongruous on the banks of the River Likouala-aux-Herbes, which meanders towards the River Congo through savannah floodplains and swamp forests. This is a place roamed by endangered forest elephants and lowland gorillas, described by one travel guide as “literally one of the most wild and remote regions of the planet by any scale or stretch of the imagination”. Beneath the dark waters of this idyll, frequented by fishermen in dug-out canoes, the Republic of Congo’s rulers claim there lies a vast oil reserve that will lure international investment and transform the country’s debt-riddled finances. But a wide-ranging investigation by Global Witness, in collaboration with Der Spiegel and Mediapart journalists, into the oil block named Ngoki - ‘crocodile’ in the local Lingala language – sheds new light on this oil project. Global Witness can reveal serious corruption risks, environmental assessments that are completely unfit for purpose, and expose claims of vast oil reserves as seemingly hollow. Oil production in this region would not only be environmentally harmful, but an investment every bit as perilous as these crocodile-infested waters.

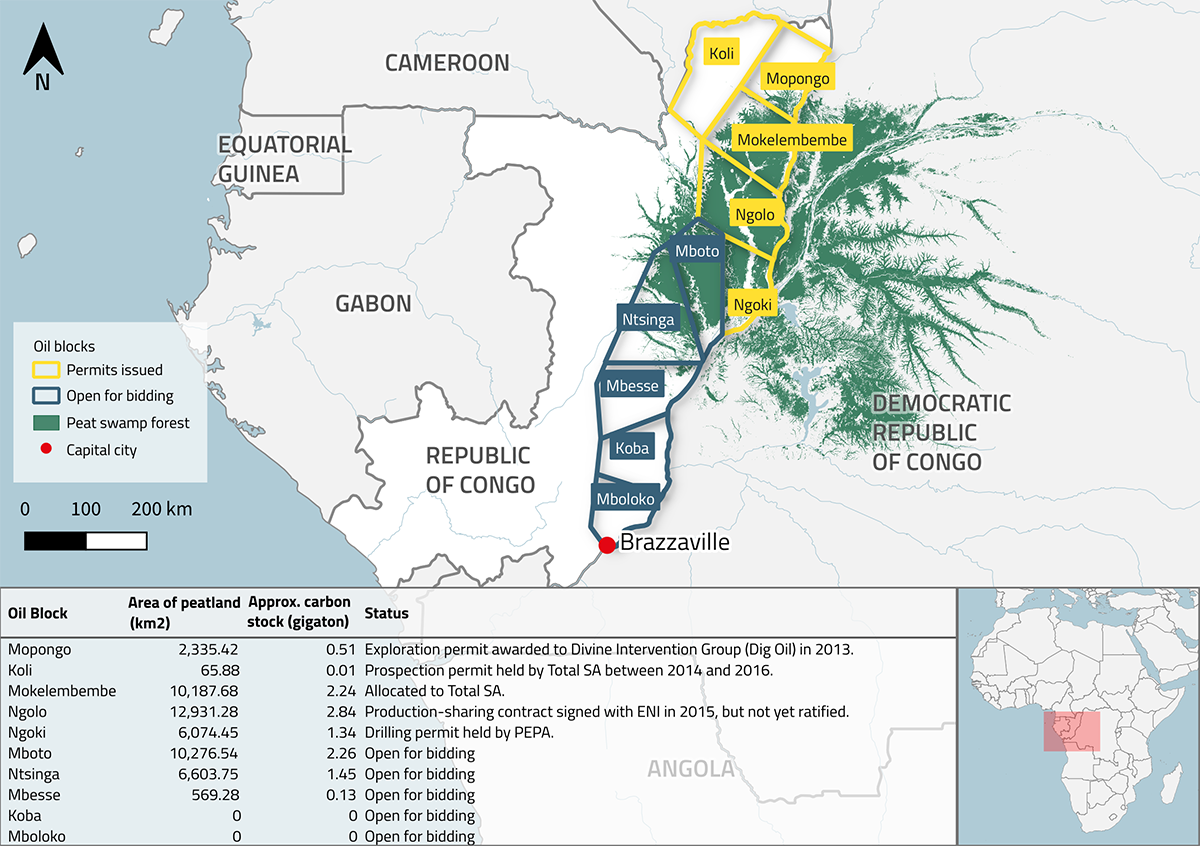

Republic of Congo’s Cuvette oil blocks

and the peatlands (peatland data from https://congopeat.net/maps). Global Witness

The Cuvette Centrale is a vast swathe of forest and wetlands at the heart of the Congo Basin. It is critical in terms of biodiversity and the global climate, forming part of the world’s second largest tropical rainforest. In 2014 British scientists made the startling discovery that the region also holds the world’s largest tropical peatlands. The Congo Basin peatlands are crucial to the global effort to combat climate change. They have been estimated to store 30 billion tonnes of carbon, equivalent to three years’ worth of global fossil fuel emissions. If this region were fully exploited by oil companies, much of this peatland would have to be drained to build roads and infrastructure, releasing stored carbon in the process. That makes the Cuvette one of the biggest carbon time bombs on the planet.

The region is also one of the world’s last frontiers for oil exploration. The governments of both the Republic of Congo and neighbouring Democratic Republic of Congo have signed various exploration deals with oil majors in the Cuvette. But so far its oil reserves have remained largely unknown and unexplored, largely due to its extreme remoteness and Congo’s difficult business climate. Congo’s government has long been keen to develop an oil industry in this region. 2019 thus saw an ongoing bidding round for new oil investors there.

A startling oil ‘discovery'

Scientists have discovered vast peatlands in the Congo Basin. Kevin McElvaney / Greenpeace

In August 2019, dignitaries gathered in President Sassou-Nguesso’s sleepy hometown of Oyo to hear the announcement of a gigantic oil discovery. The Ngoki find would purportedly quadruple the country’s oil production, putting the Cuvette region firmly on the oil map.

President Sassou-Nguesso trumpeted the discovery in a televised address to the nation a few days later, claiming: “Our country has never ducked the obligation to protect the peatlands and has no intention of doing so.” This was despite Congo “still waiting” for financial compensation from richer nations for protecting these ecosystems, he said. The president was at pains to point out that Ngoki was located not on the peatlands but their “periphery”, insisting “innovations” meant oil could be produced in a way that would “limit the impact on the environment”.

Three weeks later, the president flew to Paris to meet French President Emmanuel Macron and sign a US $65m agreement to protect Congo’s forests and peatlands, as part of the Central African Forest Initiative (CAFI). CAFI is supported by donors including Norway, France and Germany. The visit made headlines for Sassou’s arrival at this climate meeting by private jet rented at an estimated €456,000. Yet the agreement did not rule out oil or mining activities in Congo’s peatlands, merely committing to grant the peatlands a “special legal status” by 2025. The threat of oil exploration in the Cuvette was apparently of little concern to Congo’s donors.

The Central Africa Forest Initiative: a failure to protect the peatlands from oil exploration

In September 2019, President Sassou-Nguesso met Emmanuel Macron in Paris to sign a US $65m agreement aimed at protecting the Congo Basin forests and peatlands. It was part of the Central African Forest Initiative (CAFI), funded by donors including Norway, the EU, France and Germany. The funding’s objectives were set out in a ‘Letter of Intent’. This stated the aim of minimising the impact of oil extraction on the Congo’s forests and peatlands. But a closer look shows the benchmarks agreed are extremely weak. Far from ruling out peatland oil extraction, Congo only commits to produce “guidance documents and standards” on reducing the impact of oil and mining projects on forests and peatlands by 2025. A “special legal status” will be granted to the peatlands “so that they can be protected and managed sustainably” – but not until 2025.

This could be too little, too late, to stop the peatland region’s devastation by oil companies.

A Family Affair?

The oil strike was announced by a private Congolese company named Petroleum Exploration and Production Africa (PEPA). But this investigation has found that PEPA has strong links to the family of President Sassou-Nguesso. A 2018 document seen by Global Witness names the director general of PEPA as one Cyr Nguesso. Local sources say he is a nephew of President Sassou-Nguesso - the son of his eldest brother, who is described in the media as “the patriarch of the [Sassou-Nguesso] clan”. In a letter to Global Witness, PEPA’s owner said that Cyr Nguesso was selected as director general following a “rigorous selection” and on the basis of his “rich experience” in the oil sector.

Claude Wilfrid Etoka - the Ngoki project’s major shareholder. Léonard Pongo / DER SPIEGEL

The head of PEPA’s board and apparently its major shareholder, meanwhile, is Claude Wilfrid “Willy” Etoka, a high profile Congolese businessman. Mr Etoka is described by Forbes as the 10th richest person in francophone Africa and worth more than US $500 million, with a business empire structured through a myriad of companies in Congo, Switzerland, Cyprus, the British Virgin Islands and Morocco. Reportedly a close associate of President Sassou-Nguesso, he is often pictured with Denis Christel Sassou-Nguesso, the president’s controversial son who is a central figure in some of Congo’s most notorious corruption scandals. This apparent closeness to the presidential family could be a serious conflict of interest, handing Mr Etoka a potential advantage in obtaining state contracts.

One of those with knowledge of the Ngoki project is Loik le Floch-Prigent, the former head of French oil major Elf who was jailed in 2003 over his part in France’s infamous Elf Affair. This was described by the Guardian as “perhaps the biggest financial scandal in a western democracy since the end of the Second World War”. Mr le Floch-Prigent was a consultant on the Ngoki project before Willy Etoka took control. He told Global Witness Mr Etoka “works with Denis Christel Sassou-Nguesso”. The Frenchman elaborated: “The work that has been done [at Ngoki] has been overseen by Mr Etoka and therefore by Denis Christel.”

Willy Etoka denies having direct financial dealings with the president or his son. “I have friendships with the Nguesso family, that’s for sure,” he said in 2015, “but no business relationships.”

But the connections with the state appear to run deep. A closer look at Willy Etoka’s business empire – encompassing oil, agribusiness and manufacturing – shows it was built on a plethora of handsome deals with the Congolese state. His agribusiness Eco-Oil Energy operates 50,000 hectares of palm oil plantations previously run by state-owned enterprises. In 2015, the Congolese government also reportedly gave Mr Etoka’s company Congo Capital Enterprises the responsibility of privatising 46 state-owned firms across a range of sectors from logging to hydropower, acting as a broker with international investors. Most recently, he signed a joint venture with Congo’s agriculture ministry and a Chinese investor to set up a tractor factory.

Mr Etoka told Global Witness these privatisations took place in the context of the failure of many of Congo’s state-owned enterprises and the insistence of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) that they should be privatised. He said his companies have heavily invested in these ventures and helped to create thousands of jobs. Eco-Oil’s acquisition of plantations was fully in accordance with Congolese law, he said.

But the bulk of Mr Etoka’s wealth is attributable to another venture that depends on the state - his oil trading company SARPD Oil. This carved out a lucrative role as an intermediary between Congo’s state oil company, Société Nationale des Pétroles du Congo (SNPC), and major international oil traders. The IMF warned last year that a “lack of transparency about SNPC’s oil trading operations” was a corruption risk.

Oil distribution facility near Pointe Noire, Congo. SAMIR TOUNSI/AFP via Getty Images

SARPD Oil has claimed to control 60% of Congo’s fuel imports. According to Willy Etoka himself, credit from European banks was essential in growing his oil trading empire. But this investigation has learned that in 2015, his most important lender, the French bank BNP Paribas, appears to have decided his business was too much of a corruption risk to handle. The bank apparently decided to exit the relationship with SARPD Oil partly because of a close friendship between Mr Etoka and the wife of the Congolese President. It was also concerned that there was also “no transparency” as to why SARPD Oil was chosen by SNPC over other oil suppliers for its enviable intermediary role. Finally, the bank was concerned that the profit margin of 11.4% made by SARPD Oil in its role as middleman between the state-owned oil company and international traders was “high compared to the value added provided by SARPD Oil”.

Mr Etoka told Global Witness in a letter that BNP Paribas’ decision to exit its relationship with SARPD Oil was part of a broader review by the bank of its relationships with commodities firms, in response to US sanctions. He said that SARPD Oil’s profits from trading fuel with Congo were made in “complete transparency” and represented only 18% of the company’s sales. He added that SARPD Oil was selected by SNPC in line with the relevant regulations in 2005, before Denis Christel Sassou-Nguesso took up a role at the state oil company. BNP Paribas did not offer any comment.

UK court files and

documents filed at Companies House show one of those international traders trading

with SARPD Oil was Glencore, which shipped oil from the Congo and

refined fuel back in. Although there is nothing to suggest Glencore's dealings

with SARPD were improper, the

commodities giant has repeatedly been exposed by Global Witness using dubious

middlemen to secure allegedly corrupt deals around the world. In the Democratic

Republic of Congo (DRC), they dealt with Dan Gertler, a close friend of

former DRC president Joseph Kabila. Mr Gertler has since been slapped with US

sanctions, and his deals potentially deprived DRC’s people of at least 1.5

billion dollars.

Disreputable company

Meanwhile in Brazil, Global Witness reported how Glencore allegedly paid $4.1m in bribes to officials in the state oil company Petrobras, including through middlemen who were amongst the most implicated figures in that country’s iconic ‘Car Wash’ scandal. Perhaps that is why in June 2019, Bloomberg reported Glencore would stop using many of its “agents and dealmakers” under “pressure from its compliance division”. Glencore has always insisted it has a zero tolerance policy for corruption and would never knowingly employ corrupt middlemen. The commodity trader declined to comment when asked by Global Witness about its relationship with SARPD Oil.

SARPD Oil is also a shareholder in a company called Consortium SNAT SA, a joint venture with the state oil company SNPC to distribute petrol in Congo. SNAT is a partner in the Ngoki oil project. And its registration document was signed by the president’s son Denis Christel Sassou-Nguesso on behalf of SNPC in 2013 - when he was deputy director of the state-owned SNPC and in charge of its interests in the downstream oil sector. Thus we have another link between Mr Etoka, the Ngoki project and the presidential family.

Mr Etoka is keeping disreputable company with his holdings in SNAT. Its other shareholders include controversial Congolese firm Africa Oil and Gas Corporation (AOGC). Like SARPD, AOGC has acted as an intermediary between the state oil company SNPC and international oil traders. AOGC has been named in corruption investigations in both the UK and Italy and accused of making payments to companies that were owned by Denis Christel Sassou-Nguesso and paid off his credit card bills. AOGC was founded and seemingly controlled by Denis Gokana, the former head of SNPC and Presidential oil advisor. In 2019, Global Witness exposed conflicts of interest between Gokana’s public role and oil licences granted to AOGC. Mr Etoka told Global Witness that the relationship between SARPD Oil and AOGC was “strictly commercial and shouldn’t be subject to any insinuation of corruption.” AOGC did not respond to a request for comment.

Congo’s presidential family has been hit by a string of scandals. JEWEL SAMAD/AFP via Getty Images

Members of the Nguesso family have been named in a string of corruption scandals. In September 2019, the Republic of San Marino confiscated €19m from bank accounts controlled by the president following a money laundering investigation. The accounts were reportedly used to fund lavish purchases, including €114,000 spent on crocodile skin shoes. In 2019, Global Witness uncovered schemes with the hallmarks of corruption, through which the president’s children Denis Christel and Claudia Sassou-Nguesso had seemingly stolen around US $70 million of states funds between them. A spokesman for the Congolese government dismissed these allegations as “fake news”. Police in France, Portugal and Italy have also opened investigations into high-level corruption or money-laundering in the Republic of Congo. None of the Sassou-Nguesso family responded to repeated contacts from Global Witness outlining the various allegations in this report.

At the very least, the Ngoki project’s manifold links with the presidential family - plus SARPD Oil’s bank accounts being terminated by BNP Paribas - are likely to give potential investors serious pause for thought. Such investors could risk scrutiny from regulators were they to back the Ngoki oil project.

Oil majors in the Cuvette Centrale

Total and ENI are the only oil majors linked with oil exploration in this region. Total does not appear to have undertaken exploratory work, but its CEO recently said the company was ready to begin. Total has been linked with a Cuvette oil block north of Ngoki named Mokelembembe, after a mythical dinosaur-like creature spoken of by the indigenous Bayaka ‘pygmies’ of the region. During this investigation the company responded to a letter from Mediapart saying that they had been attributed the Mokelembembe block as of 31 December 2019. Total said that they were aware that the region was ecologically sensitive and would “proceed with caution”, undertaking full environmental impact assessments. This block contains over 10,000km2 of peatland rainforest ecosystem. Total’s CEO Patrick Pouyanné discussed the region’s oil with President Sassou-Nguesso during a meeting in Paris in September 2019. After the meeting, Mr Pouyanné told journalists his company was willing to undertake seismic surveys in the Cuvette to “help Congo to evaluate its resources”.

Total also held a prospecting license for an area called Koli, overlapping the Noubale-Ndoki national park, 4,000 square kilometres of contiguous lowland rainforest reputed to be the best example of an intact forest ecosystem left in the Congo Basin. The permit expired in 2016. Total told Global Witness that it is not in discussions over Koli. The Italian state oil company ENI, meanwhile, agreed a production sharing agreement for an oil block called Ngolo in 2015, although this remains unratified. The block contains an estimated 12,000km2 of peatland forest. ENI told Global Witness that it had performed no exploration activities in the block to date.

Total and ENI are backed by investors such as Credit Agricole, Barclays, JP Morgan and BNP Paribas. Such banks are currently under intense scrutiny over fossil fuel investments, and some have adopted policies over sensitive areas such as the Arctic. But few have ruled out financing oil exploration in climate critical forests and peatlands. Credit Agricole’s policy on oil investment, for example, rules out lending to projects in “wetlands covered by the Ramsar Convention”, an international agreement that aims to protect areas including the Congo peatlands.

Opening up new oil fields such as these would make it impossible to meet the Paris Agreement’s global emissions targets and avoid the most disastrous effects of climate change. Any investors could thus be saddled with ‘stranded assets’ that are unprofitable as the world seeks to reduce its carbon output. Oil-fields in logistically difficult and environmentally sensitive regions like the Cuvette Centrale present even greater risks. If ENI or Total move forward with exploration here, their financiers could find themselves supporting projects that harm some of the world’s most climate-critical rainforests.

Credit Agricole said that while ENI and Total are its clients, the bank was not providing specific project financing for oil exploration in the Cuvette Centrale. Barclays, BNP Paribas and JP Morgan made no comment.

Peatlands in peril

Congo’s peatlands contain vast carbon stores. Kevin McElvaney / Greenpeace

In September 2019, Congo’s Environment Minister Arlette Soudan-Nonault brushed aside concerns about the environmental impacts of drilling in Ngoki. She told Le Monde it “is not in the peatlands”. The Congolese government has also given promises that drilling would be done in a way that has “limited impact”. But by analysing the best available maps of the peatlands, Global Witness has calculated the Ngoki oil block as a whole could contain over 6,000 square kilometres of carbon rich peatland. That is an area more than twice the size of Luxembourg. This peatland contains an estimated 1.34 gigatonnes of carbon – greater than the annual emissions of Japan if it were all released. The exact impact oil exploration could have on this fragile ecosystem has not been assessed. But a landmark 2019 study on the Congo peatlands warned of “risks of oil spills and wastewater damaging the peatland ecology”, plus access roads and pipelines contributing to deforestation and desiccation.

A Global Witness analysis of documents related to the exploration found the peatlands are indeed under threat from the worst impacts of oil drilling, with little meaningful effort to protect them:

- The Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) for the Ngoki oil wells does not make any analysis of the potential impact of drilling on the peatlands, noting only that “a detailed study (of the peatlands) is necessary”. The EIA is therefore completely unfit for purpose. Furthermore, Global Witness has learnt that this EIA was based on studies done in 2013 – before the Congo Basin peatlands were discovered by scientists in 2014.

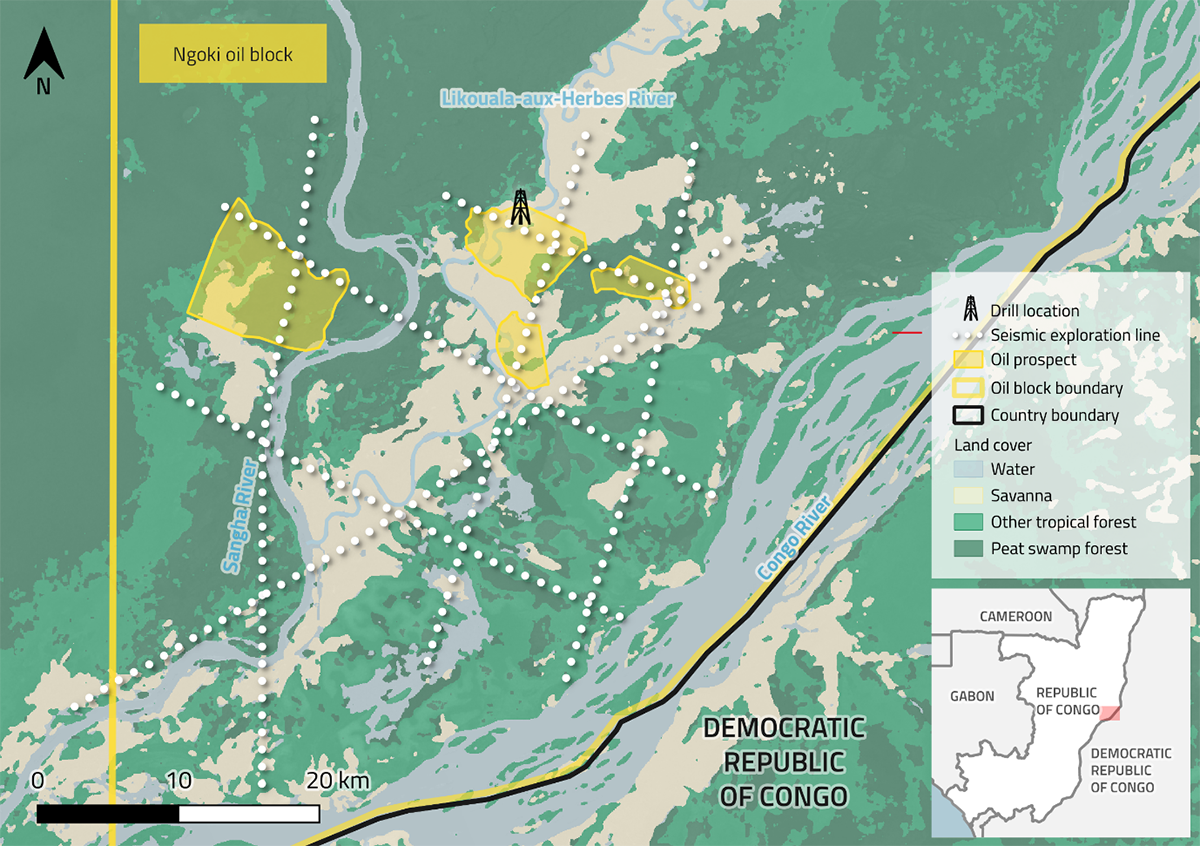

- Exploration reports seen by Global Witness identify four prospects in Ngoki identified during seismic surveys in 2008 and 2009 where oil drilling would take place (see fig. 2). An oil prospect is a potential underground reservoir which geologists believe may contain hydrocarbons. Two of the four are directly beneath areas of sensitive peatland. This contradicts the claims of Congo’s Environment Minister. Drilling in these areas could require draining and destroying the peat, and risk damage from oil spills.

- The riverside Likouala-aux-Herbes site where drilling has already taken place is not directly situated on peat. However, the scientific data suggests the well is flanked both to the north-west and south-east by major peat deposits. These are around 3km from the oil well and on a river connected to peatlands. The potential for them to be exposed to oil spills or wastewater pollution, or damaged by infrastructure, does not appear to have been assessed.

Ngoki block - location of oil activities and

peatland forest (peatland data from https://congopeat.net/maps). Global Witness

Global Witness’s concerns are shared by Congolese civil society. In August 2019, an open letter was signed by prominent Congolese civil society activists expressing doubts about the oil project. They questioned whether it would “spare the rich peatlands and allow the country to meet its climate commitments, when Congo's track record in terms of governance is well known”.

Mr Etoka told Global Witness: “Compared to coastal oil operations, which can produce traces of marine pollution, oil exploration in the Cuvette presents no risk of environmental disturbance.

“The president of the Republic of Congo, who is in charge of protecting the Congo Basin, would not have authorised us to explore for oil there, if there was any evidence of such risks.”

Mr Etoka also said that the exploration was preceded by an environmental impact assessment, approved by Congo’s Environment Ministry, and that the peatlands were “outside” of the Ngoki oilfield.

A troubling backstory

Global Witness also retraced the tangled history of the Ngoki block, examining unpublished exploration data and consulting informed sources to see how credible the claims of a huge oil discovery really are. The findings are another cause for concern.

A colourful cast of characters have wrangled over the rights for oil in the Ngoki block. In 2006, the Congolese state oil company SNPC signed a production-sharing contract for Ngoki with Pilatus Energy, a company owned by Abbas Al Youssef, an Emirati businessman and former air force pilot. Al Youssef reportedly started out as a middleman in controversial arms deals, growing wealthy by facilitating arms and aircraft sales to the Middle East for European companies. Investigative journalists from Der Spiegel and Mediapart have linked the commissions paid to Al Youssef by arms companies to bribes paid in countries such as Egypt– something Al Youssef denied. Al Yousef’s man in Congo was the aforementioned former Elf boss Loik le Floch-Prigent, by then released from prison.

In 2008, le Floch-Prigent and Al Youssef started the search for oil in Ngoki, conducting seismic exploration during the brief dry season in a region underwater for much of the year. But the partnership was to take a bizarre turn after Al Youssef lost almost $50m to fraudsters posing as the family of the deceased president of Ivory Coast. In 2012, le Floch-Prigent was arrested and served five months in a Togolese prison, accused of aiding the fraudsters - something he has always denied. Al Youssef had already sunk over $60m into the oil project. But with his business empire in deepening financial trouble, Pilatus Energy was forced to look for an investment partner.

Enter Willy Etoka. With a promise to clear the project’s growing debts, he joined the project in 2013 and the abovementioned PEPA was created. This new company was jointly owned by Al Yousef’s Pilatus with 70% of the shares and Mr Etoka’s SARPD Oil holding 30%. A source close to Pilatus told Global Witness that upon acquiring this stake, Mr Etoka simply took control of the company, and that Mr Al Yousef was no longer invited to all board meetings despite allegedly continuing to hold a majority of shares. By 2016, Willy Etoka held over 99% of PEPA’s shareholding. A source close to Mr Al Yousef insists he never received payment in recompense. Subsequent attempts by Pilatus to challenge the process through the Congolese courts came to nothing. Mr Etoka now had full control of the Ngoki project. In an industry hardly known for its transparency and sense of fair play, the saga still manages to raise eyebrows. This unsavoury tale should be yet another red flag for potential investors.

Mr Etoka told Global Witness his takeover of PEPA was done in order to "boost" the faltering company, which was hampered by Mr Al Youssef’s failure to inject capital into the project. The transfer of shares was authorised by Congo's commercial court, he said. Mr Al Youssef did not respond to Global Witness’s enquiries.

Doubts cast on oil find

But as we will see, all this manoeuvring may yet come to naught. For the punchline to this remarkable series of events is that there may even not be enough oil in Ngoki to make it economically viable. Congo’s big announcement was met with deep scepticism in many quarters. One oil expert described PEPA’s claims that the deposit could contain 359m barrels of oil and produce over 900,000 barrels per day as “ridiculous”. Others questioned how such a large deposit could have escaped the attention of major oil firms.

Documents seen by Global Witness give strong indications that oil production in this region may not be viable after all. These show that Total and Shell both rejected offers to invest in the Ngoki oil project back in 2015, after viewing the results of a seismic survey. In correspondence seen by Global Witness, an exploration manager at Shell explained this decision by saying that any oil deposits were likely of “modest size”, and that “given the surface risk and operational challenges in this area, the 'size of the prize' would have to be very substantial”.

Global Witness has also analysed seismic and chemical surveys undertaken in Ngoki prior to 2015 by PEPA’s predecessor, Pilatus Energy. These too cast doubt on the credibility of Congolese claims of a major oil find, specifically the 359m barrels figure. A geologist with extensive oil industry experience told Global Witness that based on the known exploratory work carried out so far, it would be impossible to say with any certainty that there might be significant amounts of oil and gas in the basin. The surveys - a 2D seismic survey coupled with the results from one exploratory well - are simply not enough to prove that oil and gas accumulations exist and what size they might be.

Loik le Floch-Prigent told Global Witness: “This is an area that I have studied, and it’s absolutely not possible to judge the size of reserves at this stage.

“The figures announced by PEPA have no scientific or technical basis. It’s a very risky investment.”

Mr Etoka denied attempting to mislead investors about the oil discovery, and said his company’s claims were based on “reliable data that will be confirmed shortly by production tests that are in progress”. Drilling, he insisted, had revealed oil reservoirs measuring 89m in depth.

These rebuttals notwithstanding, the oil magnate’s questionable dealings and Congo’s reckless handling of environmental issues mean there is serious concern that any oil investments in the Cuvette will end up as stranded assets, rendered unprofitable as the world transitions to a low-carbon economy. The Congolese government may still hope the Ngoki “discovery” will bring investors flocking to the region. But a toxic mix of environmental harms and the whiff of possible corruption should prove too much to stomach for all but the most reckless of investors.

Oil in the Republic of Congo: a history of scandal

A series of headline-grabbing corruption scandals have embroiled the major players in Congo’s troubled oil sector.

The Elf Affair. The trial of one of France’s biggest ever corruption scandals concluded in 2003. This laid bare a system put in place by the French state-owned oil company to pay millions of dollars in kickbacks in African countries where Elf had oil operations, including the Republic of Congo.

Gunvor. At a 2019 trial in Switzerland, the giant commodity trader Gunvor was found to have failed to prevent its employees paying bribes in order to secure oil contracts in Republic of Congo and Ivory Coast. Gunvor was ordered to pay almost 94 million Swiss francs (US $94.8 million).

ENI. The Italian oil major is embroiled in a corruption probe by authorities in Italy, over agreements signed by its Congo subsidiary with the Congolese oil ministry. ENI denies it was involved in any illegal conduct. Investigations continue.

Recommendations

- Oil majors, in particular Total and ENI, should publicly state that they will not invest in oil exploration anywhere in or around the Congo Basin peatlands, on environmental grounds.

- French banks should report on risks linked to financing or providing financial services to industrial developments in or around the Congo peatlands under their 2020 Vigilance Plan, report on due diligence processes in place, and identify risks and mitigation measures to prevent these.

- In its enforcement of the Duty of Vigilance law the French government should ensure companies, including financiers, are required to report any involvement in projects that would damage primary tropical forests, critical wetlands or peatlands.

- Banks should rule out lending to any new oil and gas projects, and particularly those which threaten the destruction of carbon sinks such as tropical rainforests and peatlands.

- Donors to CAFI, including Norway, France, Germany and the EU, should urgently require the halting of any oil, mining or agribusiness projects in or around the Congo peatland in advance of the peatlands being accorded a special legal protected status.

- The EU should adopt legislation to require all companies and financiers to undertake, be accountable to, and report on due diligence to identify, mitigate and prevent human rights and environmental risks associated with their operations and investments.

Find out more

You might also like

-

Briefing The Spotlight Sharpens

Global Witness has exposed strong evidence of high-level corruption relating to four of Italian oil giant Eni’s licences in Republic of Congo.

-

Briefing Rigged: where has Republic of Congo’s oil money gone?

Our analysis of previously hidden oil sector documents from Republic of Congo reveals major indicators of corruption and a sector skewed in favour of foreign oil companies, including Total, Chevron and Eni

-

Report Total Systems Failure

We reveal systemic illegal logging by a major European company in the Democratic Republic of Congo, while Norway and France are on the brink of funding expansion of the country’s industrial logging sector